By Manuel Paz y Miño, Editor of Eupraxophia and Neo-Skepsis.

Swedish author Christer Sturmark (1964) has a master's degree in computer science, and he is an information technology entrepreneur, publisher and secular humanist activist.

Christer Sturmark

(Photo from fritanke.se)

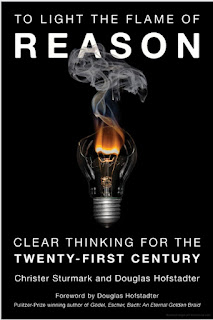

His book has been originally written and published in Swedish with the title Upplysning i det 21: a århundradet [Enlightenment in the 21st century] and translated into English by Douglas Hofstadter--a winner of a Pulitzer award--. It has a foreword by him, another one and a prelude by author, 2 parts with a total of 14 chapters and each one of them ends with an interlude or short article, all of them focus with or a philosophical view or a scientific one. The original version has 18 chapters, some of them with a focus in issues on Sweden, and it was launched in 2015 by Sturmark’s publishing house Fri Tanke (Free Thought) where were translated into Swedish and published also works by Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett, Rebecca Goldstein, Mikhail Gorbachev, Andrew Hodges, Steven Pinker, etc. (p. xii).

Author’s foreword remembers some conspiracy theories, the prohibition of words and pictures making fun of religion around the world threatening their authors with death, as was ordered by Ayatollah Khomeini against Salman Rushdie in 1989 because of the mockery of Muhammad in his book The Satanic Verses (an unsuccessful attempt against him has been made on August 12, 2022 at the New York state), and other cases against freedom of speech and human rights in several European and Asian countries (pp. xv-xvi).

Sturmark’s antidote to all this is a revival of “enlightenment values,” the art of clear thinking and bring about a renaissance of secular ethics. He says

I also harbor a hope that such ideals could come to be included in the school systems throughout the world. Today, many schools could be said to be in a state of crisis. It’s not so much due to problems of discipline and behavior but, rather, to a loss of perspective about the nature of knowledge and understanding. Students in schools and universities throughout the world need to be exposed to a more philosophical approach; they need to have more exercises in careful and clear thinking, greater awareness of life’s complexities, and deeper probing into the nature of human existence. Only when we truly recognize ourselves as reflecting, conscious humans can we fully participate in life and improve it, not only for ourselves but also for others (p. xvii).

But in fact, societies and their school systems throughout the world are not the same, they have different approaches and developments: ones more attached to religious or scientific views than others. Some countries are still in their Middle Ages and even with their own Inquisitions so they need to reach to their own Enlightenment sooner or later.

Although Sturmark is known as a polemicist and critic of religious beliefs in his country, he has not only non-believers as friends but also believers (p. xix) as a tolerant secular humanist and human being that he is.

Author’s prelude recollects too several cases worldwide of irrational, religious and superstitious mistreatments, abuses and crimes--included denying abortion to women at health risk, refusing cancer and medical treatment and blood-transfusion to children, attacking, criminalizing or killing individuals from religious minorities, homosexuals, blasphemers, non-believers, and supposed witches (pp. xxii-xxv).

Part I of the book, “The Art of Thinking Clearly,” deals with diverse topics among them the following: Tools and Compass Needed in the Quest for Knowledge (Chapter 1); Reality, Knowledge, and Truth (Ch. 2); Grounds of One’s Convictions (Ch. 3); Theories, Experiments, Conclusions, and Science’s Essence (Ch. 4); Wonderful but Easily Fooled Brains (Ch. 5); Naturalism, Agnosticism or Atheism (Ch. 6); Godness, Evil, and Morality (Ch. 7); Beliefs in Strange Ideas (Ch. 8).

Part II of the book, “The Pathway to a New Enlightenment,” has subjects on Fanaticism, Extremism, and Christian-Style Talibanism (Ch. 9); Evolution, Creationism, and Anti-science (Ch. 10); Secular Enlightenment (Ch. 11); Awe, Politics, and Religion (Ch. 12); Freedoms, Rights, and Respect (Ch. 13); Faith, Science, and How Schools Talk about Life (Ch. 14).

In the afterword, author shows himself as hopeful and a believer in reason and science, in spite of war, populism, nationalism, and racism, and at the same time he has good reasons to be optimistic about the progress of humankind: “the risk of dying from violence today is lower than ever before in history. We live longer, we are healthier, more children are allowed to go to school, and fewer people are starving” (p. 324).

The scientific, philosophical, humanist and skeptical approaches in the chapters of Sturmark’s book--that will be published also in Chinese, Russian, and Korean, and we hope in Spanish too--, recalls us Paul Kurtz' The Transcendental Temptation: A Critique of Religion and the Paranormal (Prometheus, 1986, pp. 500) translated already into Russian and Spanish (Lima: EFA, 2008), and also Michael Shermer's Giving the Devil his Due: Reflections of a Scientific Humanist (Cambridge University Press, 2020, pp. 366).

No comments:

Post a Comment